How to Make Decisions Asynchronously – And Avoid Yet Another Meeting

A 5-step guide to get real work done and clear your calendar for good

“We need to schedule another meeting to finalize this.”

Another decision-making meeting ends with no resolution in sight. The only agreement? To schedule yet another meeting to continue the conversation.

How many times have you experienced this?

Unfortunately, you’re not alone. I’ve heard this repeatedly when helping organizations improve their decision-making process. Yet, when I suggest experimenting with an asynchronous approach, leaders react with skepticism. Meanwhile, frustration continues to grow as meetings exacerbate team dysfunctions.

People come unprepared. There’s no clear understanding of the problem, context, or implications. Everyone jumps to show they’re the smartest person in the room. The entire team spends hours solving the wrong problem, and the rush to move forward dismisses outliers, resulting in shallow agreements.

Unsurprisingly, only 20% of executives say their organizations excel at decision-making, according to McKinsey. Everyone agrees that most of the time they spend making decisions is ineffective.

Every delayed decision carries a triple cost: financial waste, lost opportunity, and team friction.

Your top talent grows frustrated with the indecision. As timelines compress, people are forced to execute half-baked ideas. Your team loses faith in your ability to lead while your competitors gain critical market advantages.

What if the solution isn’t better meetings but a different approach altogether?

Asynchronous decision-making can free up both your calendar and your mental bandwidth. Today, I will share the path that has consistently helped my clients improve decision-making and move forward with conviction.

Let’s explore how it can work for you.

How Async Can Lead to Better Decisions

Want to improve how your team makes decisions? The solution isn't better meetings. It's fewer meetings with better thinking before and after them.

Shopify, Voys, Atlassian, and other high-performing organizations have discovered a powerful alternative: asynchronous decision-making systems that produce clearer thinking, broader input, and faster implementation.

Asynchronous decision-making has multiple benefits:

Giving people time to reflect in a better headspace

Integrating diverse perspectives without loud voices taking over

Slowing down the analysis speeds up decision-making and implementation

Understanding the nuances, implications, and misalignments

Documenting every stage facilitates understanding and, most importantly, commitment

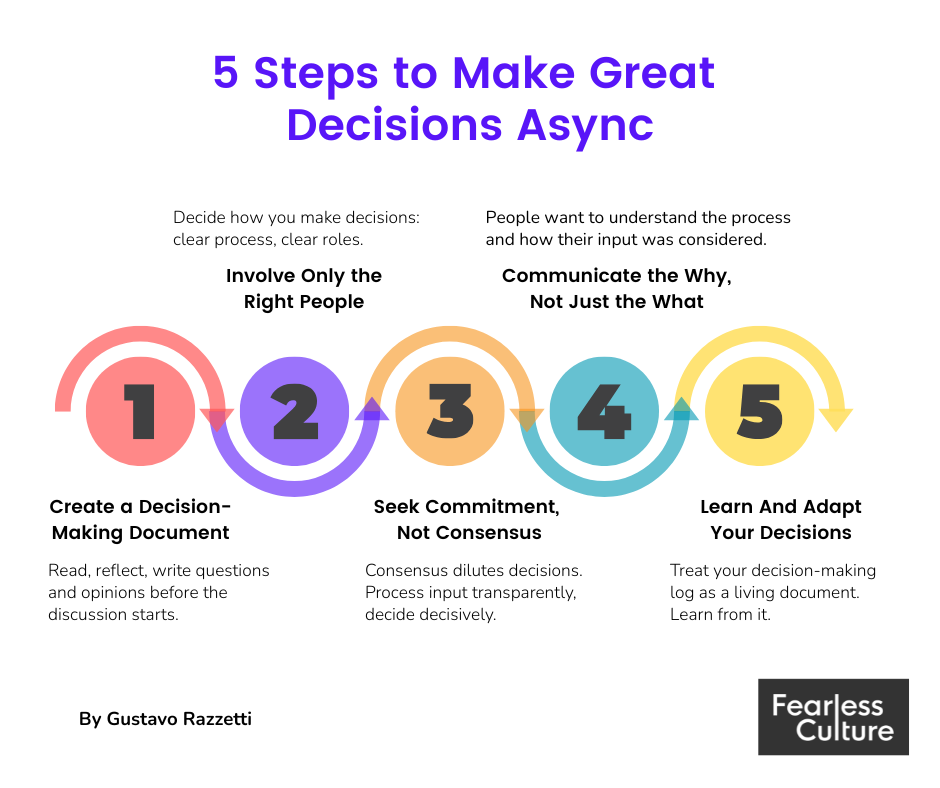

Here are five actionable steps to help you get started. Adapt them to your specific needs. The goal is to have an async-first decision-making approach, not to eliminate all meetings. Use meetings as a last resort – not the central tool – of your decision-making process.

1. Create a Decision-Making Document

Shallow discussions lead to shallow decisions.

In most organizations, important decisions happen in real-time discussions where clarity is sacrificed for convenience. Synchronous meetings reward quick thinkers and confident speakers, not necessarily the best ideas. Facts blend with opinions, context gets lost, and multiple conversations happen simultaneously – but nothing is resolved.

The result? Decisions are based on incomplete understanding, influenced more by who's in the room than by rigorous thinking. Everyone leaves the meeting with different interpretations of what was decided, leading to misaligned execution and endless debates.

The solution: Write before you discuss

Jeff Bezos banned PowerPoint at Amazon not just because he was tired of endless presentations, but to push executives to clearly state the problem at hand.

Instead, he required his leadership team to write a six-page narrative memo. This practice forces people to be clearer and more specific, discriminating between what’s important and what’s not. Most importantly, it prepares everyone ahead of time. People can read the memo, reflect on the problem, and write questions, comments, and suggestions before the discussion starts, regardless of whether it happens asynchronously or live.

Creating a decision-making document levels the playing field between talk-to-think and think-to-talk members. It also provides a permanent record for future reference.

A well-structured Amazon 6-pager typically includes:

Introduction: What's the decision about? Why now?

Goals: What does success look like? What metrics matter?

Tenets: What principles or values guide this decision?

State of play: What's happening today? What data matters?

Lessons learned: What's worked or failed before?

Strategic options: What are the choices, trade-offs, and implications?

Appendix: Supporting data, charts, and models (keeping the main document narrative-driven)

A decision-making document ensures decisions are considered from multiple angles. Writing a good structure memo isn’t easy, but the time spent is worth the investment.

I love Notion’s usability and features for documenting decisions. Other tools to consider: Trello, Twist, or Google Docs. Avoid chat platforms like Slack – they work for simple decisions, not complex ones.

2. Involve Only the Right People

Start by deciding how you make decisions.

Helping teams make better decisions, I often observe how many struggle to find the right balance. They either involve everyone in the process or keep them in the dark. The real problem? They lack a clear decision-making process.

People often misunderstand their roles – some assume they’re shaping the decision when they are only meant to advise. Key subject matters aren’t consulted until after decisions are made. Team members have different expectations about who makes the final call, leading to frustration and a lack of commitment.

The result is decision limbo: A state where decisions are never final and remain perpetually “under consideration” because the team is not aligned on how to make decisions.

The solution: Define clear decision roles

The goal is not just to involve fewer people but the right ones – those with clearly defined roles. The key is giving more people a voice but fewer a vote.

For any significant decision:

Establish transparent decision rights upfront (ideally one person, never more than two)

Clarify who will provide input – typically 3–5 stakeholders (subject matter experts or roles who will be affected by the decision)

Set clear expectations about the decision method and how input will be considered

Establish clear boundaries on decision authority and timelines

Consider, for example, McKinsey's DARE framework:

Decider: The final decision maker. Ideally, there is just one.

Advisors: Able to influence or shape the decision. They can consult, but they don’t decide.

Recommenders: Subject matter experts who provide in-depth perspectives and/or those closer to the problem. Both present an angle the decider might be missing, as well as options to provoke rich conversations.

Execution members: Those who will implement the decision – they must be informed and committed to supporting it.

3. Integrate Feedback: Seek Commitment, Not Consensus

The consensus trap dilutes decisions.

Most organizations fall into one of two feedback traps. Either they cherry-pick input that supports a predetermined direction, or they try to incorporate everyone's suggestions to avoid hurting anyone’s feelings. Both approaches fail, creating superficial buy-in that nobody truly supports.

The solution: Process Input Transparently, Decide Decisively

High-performing organizations don't seek consensus – they seek commitment. The difference is crucial. Consensus means everyone agrees with the decision. Commitment means everyone supports implementing that decision, even if they initially disagreed.

Creating commitment requires two elements:

1. A transparent process for gathering and genuinely considering feedback

2. Decisive leadership that makes the final call based on principles, not popularity

After collecting feedback on your decision document:

Summarize key findings showing major themes (avoid dismissing individual warning voices)

Note which suggestions were and were not incorporated (and why)

Describe the final decision and the reasoning behind it

Circulate the updated document/link to key stakeholders and everyone affected

At Buurtzorg, before making a significant decision, CEO Jos de Blok posts his thoughts on social media, where all 10,000+ employees from the Dutch healthcare organization can comment. Within 24 hours, de Blok receives dozens – sometimes hundreds – of comments. People’s input informs his analysis and thinking.

This approach appears to contradict the principle of limited stakeholders I suggested before. But there's an important distinction: While input is broad, consensus is not the goal.

Buurtzorg reserves this approach for major company-wide changes. It works because the method combines complete transparency with decisive leadership. Employees are clear that while de Blok values everyone's perspective, he still owns the final decision.

4. Communicate Decisions Clearly - The Why, Not Just the What

Announcements without context are not enough.

Making the right decision is just half the story. Successful execution depends on clear communication.

People don’t want to be told what to do. Before committing to change, they want to understand the “why.”

Share what was decided, the process, and why some feedback was considered or discarded. While your team members may not always agree with your solution, they will appreciate that there’s nothing to hide.

Transparency prevents skepticism and shows respect for people’s contributions.

The solution: Don’t just share a solution. Share context, too.

Effective leaders know that how you communicate a decision is almost as important as the decision itself. Significant decisions should include:

The decision itself, stated clearly upfront

The process used to reach the decision (who was involved, how input was gathered)

Core reasoning and criteria that guided the choice

Alternatives that were considered and why they were discarded

Implementation plan with clear owners and timelines

Encouragement of clarifying questions and objections

When GitLab revised its compensation model, it decided to be completely transparent. They shared the approach but also the rationale. You can check it out here even if you’re not an employee. The company supported the announcement with videos explaining the whole process. Even better, they encourage employees to email total-rewards@gitlab.com when leaders fail to follow the process.

Video is a powerful tool to share decisions – and the process. It brings the context and the "why" behind a decision to life, making it easier to return to it when needed. I like Vidcast – its AI makes it easier to search videos and skip to what matters.

5. Learn And Adapt Your Decisions

Don’t just create a decision-making document – learn from it.

Many organizations struggle with the fear of making decisions. I see this way too often. They treat a decision like a life-or-death situation. However, most decisions are reversible.

As Richard Branson noted, "In business, if you realize you've made a bad decision, you change it." But how can you recognize a bad decision if you've lost track of why you made it?

Deciding is like sailing. You set a clear destination, but external forces will get in the way. Wind, undercurrents, and waves will push you off course. Wise leaders know that no decision is perfect – or even final. They continuously sense changes in the context and course correct.

The Solution: Treat your decision-making log as a living document

Forward-thinking organizations create searchable, evolving records that capture not just what was decided but the full context and subsequent learning. These records serve as both organizational memory and a foundation for adaptation.

For instance, Farnam Street uses a decision journal to encourage learning. It helps you treat decisions as fluid, not rigid. Reflecting on past decisions (and the mental process) prevents us from making the same mistakes.

Awell Health adopted a “decision page” method, as I described in my book Remote Not Distant. The Belgian health tech startup made 40 critical decisions asynchronously in the first four months. This approach, though time-consuming, helped Awell make smarter, faster decisions. Even better, it promoted a culture of transparency by making the decision-making document available to everyone.

Slowing Down Makes You Faster

The immediate objection to asynchronous decision-making is always the same: "We don't have time for all this writing and process. We need to decide now!"

This urgency illusion is exactly why organizations remain stuck in meeting hell. The time you think you're saving by skipping thoughtful work will haunt you later. Those quick discussions will multiply into endless follow-up meetings as confusion, misalignment, and resistance inevitably surface.

The five steps I’ve covered might seem like a lot of extra work. Yes, they are. But they’re also an investment that will save you time down the road.

Next time you're tempted to call yet another meeting to "align" on an important decision, ask yourself: Do you want the theater of decisiveness or actual results?

Give async decision-making a try.

If you’re serious about experimenting with async decision-making, give me a call. Click here to schedule a free consultation.

Some great insights here, especially the Bezo decision document.

And OMG the over democratic decision making. Just decide for god sake. Since when are companies democracies? Since we all decided we didn't want to be held accountable for mistakes.

Well suck it up cupcakes, everyone screws up. You are not infallible. No decision is a failure, making no decision is the only failure. Making the wrong decision for the right reasons and learning from it is success

This is so on point, Gustavo. I'm seeing this "decision-making inertia" in almost every executive team so far. I've seen only a handful of exec teams that have decision-making down to a rigorous process and effective CEO's know that they must make the call, when a decision are in a 'tie". Patrick Lencioni also speaks to this very subject when he states that leadership teams that are unable to have healthy conflicts -and have the necessary trust which is fundamental - are making mediocre decisions. Consensus is the worst guideline for decisions that actually support a company's growth. Thank you for the different frameworks you're mentioning in your article (DARE and 6-page decision memo & the communication guidelines) . Really useful and I want to try them out.